Pandas Big Endian - Little Endian Mismatch Fix

This blog post focuses on a strange, recurring issue I would run into while working with some astronomy data, and contains both a description of how I came across the problem, a brief theoretical background on where the issue arises from, and how I was able to resolve the issue.

The Problem

I have run into this odd, recurring issue when working with older files of astronomy data, both in the .fits and .sav format (from IDL specifically). This issue arises from pandas, which in some cases will read the file fine, but will throw the following error when attempting to operate on that data, and in others will throw the error on attempting to read the file;

1

ValueError: Big-endian buffer not supported on little-endian compiler

It took me some time to track down how to solve this issue, and even then I didn’t particularly understand it; My original solution involved bouncing the data between an astropy table and a pandas dataframe, which resolved the errors, but didn’t really help me get a better understanding of what the source of the problem was.

Fast forward a couple of months, and I ran into this problem again, this time when trying to load in a large IDL save file that contained some data I needed. At this point, I sat down and spent some time researching the actual concepts involved, and getting a better handle on why this problem arises in the first place.

What Even Is An ‘endian’, Anyways?

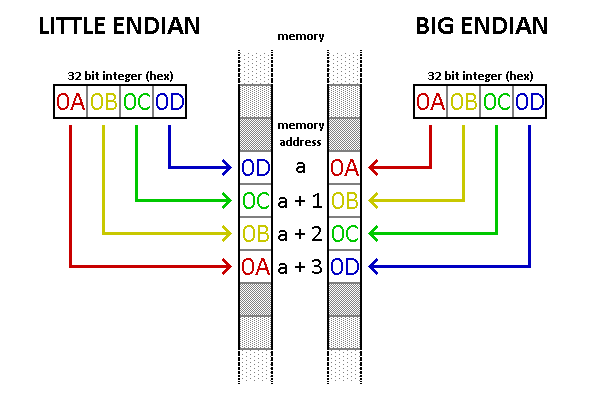

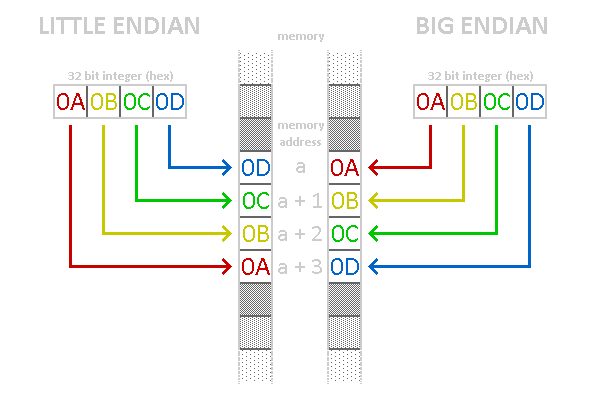

From a quick visit to the relevant wikipedia article, the general gist is that ‘endian’ refers to how data is stored in computer memory. The image below uses a 32 bit integer as an example, however this can be extended to essentially any small unit of data that is stored in memory.

A diagram depicting the difference between endian configurations

A diagram depicting the difference between endian configurations

In memory, the bytes of a value can be stored in two orders; front to back, and back to front. This orientation is what ‘endian’ refers to; in a little endian configuration, the least significant byte of data (the little end) is stored first, with the bytes following increasing in significance, whilst the big endian configuration is the opposite, with the most significant byte of data (the big end) being stored first, and the other bytes following in decreasing order of significance.

There doesn’t seem to be any obvious benefit or detriment for either configuration, however I am sure that someone with more technical experience in computer science would be able to articulate the functional tradeoffs between the two approaches. Perhaps it could relate to how quickly the computer can read the value, with the big endian configuration allowing the computer to resolve the ball-park of the value first, before chasing down further precision, but this is just an idle guess.

The endian-ness of memory also seems to be platform specific, which would help elucidate why my windows 10 machine would encounter the error, whilst others who helped check my code on a mac machine did not encounter any errors.

But Why The Problem?

Since endian-ness is platform specific, but most normal files can be easily transported and read between different operating systems, the issue likely lies in the older, more esoteric file formats.

Perhaps these older formats (.fits and .sav) are encoding integers in such a way that their specific endian-ness is being encoded as well. This would explain why other files, that are simpler or more modern, don’t encounter problems in the same way.

Alright, But How Do I Fix It?

With that theoretical background in mind, we can move forwards towards trying to resolve the problem.

There exist two basic variants of this problem; a .fits file that refuses to be read into python as a dataframe, and a .sav file that can be read, but will error if you attempt to interact with its values in any substantial way.

FITS File Variant

My solution for this variant is fairly straightforward, if indirect. I used the astropy package, and specifically it’s Table class to load in the file as a table, then use the to_pandas() method available to Table objects to convert. This process seems to clean the resulting dataframe of any lingering endian-ness mismatches, and leaves it ready for further use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

from astropy.table import Table

import pandas as pd

#this creates a table object from the data in the file

# this cleans any endian mismatch in the process

temp_table = Table.read(filename, format='fits')

#this converts the table object to a pandas dataframe

# I personally find pandas dataframes more widely useable

dataframe = temp_table.to_pandas()

SAV File Variant

This variant is a little more insidious, as the IDL .sav file can be loaded using scipy.io without issue, and otherwise doesn’t present any errors when viewing the values. The error only occurs when you attempt to modify, delete, or compare against any of the values in this data.

One interesting thing I noticed while experimenting is that strings did not cause problems, and could be loaded directly from the file without raising that error. Following from this, it seemed that specifically the numbers (integers specifically and perhaps floats) encoded in the file would cause the error if they were loaded directly.

My solution to this is again somewhat indirect; using the numpy .astype() method to convert the data to a float type has the side effect of resolving any endian mismatch, which is fairly convenient.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

import numpy as np

#the .astype() command can be used with numpy arrays

# mismatch_arr contains the misbehaving data

# clean_arr no longer contains mismatched endian-ness

clean_arr = mismatch_arr.astype('float')

#applying this to a whole dataframe can be a bit more tricky...

# iterating through each column as a series would be one approach.

Final Thoughts

I am continuously reminded by problems like this just how complex and intricate the systems I interact with really are. Prior to stumbling on this, it had never crossed my mind that memory could have such directionality, even for something as simple as an integer. It boggles my mind just how many similar little decisions and details must lie in the miles-deep strata of features and technical depth that support even the relatively simple programming and research I engage in.

Computers are just so stinkin’ cool.